Being invisible and without substance, a disembodied

voice, as it were, what else could I do? What else but

to try and tell you what was really happening when

your eyes were looking through?

—Ralph Ellison, Invisible Man

Disembodiment

August 3, 2019. El Paso, Texas

At 10:15 a.m., a twenty-one-year-old aspiring terrorist named Patrick Crusius posts a 2,356 word manifesto on the internet, outlining his justification for the act he plans to commit sometime within the next six minutes. He writes: This attack is a response to the Hispanic invasion of Texas… He’s driven eleven hours from his home in Allen, Texas, all the way to El Paso, my home. He’s aware that our city of almost 900,000 residents is approximately eighty percent “Hispanic.” He’s done his homework. At around 10:21 a.m. he walks into the Cielo Vista Walmart on the east side of town carrying a semi-automatic rifle and opens fire on families who are there to buy school supplies for their children. Employees hear gun shots and see people running. They hurry and direct people to the back doors. But the terrorist is now walking around the store blasting round after round, and he does not stop. Eyewitness accounts tell us that a man and his aging mother ducked between toy machines to hide. A child was left alone but then was quickly rescued by a stranger before the man started shooting at him. An old man shielded his family but then was instantly shot and killed. In minutes blood is splattered on the floors and between the aisles. The terrorist strolls slowly through the store, picking off victims randomly for ten to fifteen minutes more. After which, he returns to his car and drives away. Minutes later he is captured “without incident,” and arrested. In all, the terrorist has killed twenty-three people and wounded twenty-four others. I receive a text:

Active shooter in El Paso happening right now!

It’s from my mom. I can almost hear the fear in her tone. And then:

Are you and the kids okay?

I respond by telling her that we haven’t arrived in El Paso yet. We’re still en route. We had left California early that morning and were driving home as it was happening. We arrive that evening and, not owning a television, the kids and I sit on our couch and check the internet for updates.

“It happened at the Walmart near the Cinemark Theater,” Rumi says, “on the east side.” We live on the west side of El Paso, but we’re familiar with the area because it’s near the reptile shop where we get supplies for Salvador’s bearded dragon.

The next morning, I decide we need to get away from the news and out of our heads. The streets are sparse and quiet. Everywhere we go people are solemn. At the gas station. At the park. The overall mood reminds me a lot of what it felt like in the days after the September 11th terrorist attacks. A collective grieving hangs in the air. El Paso is mourning.

The next two days we mostly stay home. We’re in a new house and so we focus on settling in. But there comes a point where we need groceries and other products, and so it makes sense that we should go to Walmart, which is just two blocks from our house.

As we approach the parking lot, I can sense Rumi’s apprehension. We’ve managed to avoid the discussion, but now we are faced with it. She admits that it’s all taking a toll on her. She’s “afraid of what could happen next.” I remind her that El Paso has consistently been ranked among the top three safest cities in America. A statistic that we’ve touted for all the years we’ve lived here.

“It doesn’t feel that way anymore,” she says.

“Going into Walmart is part of the healing,” I offer. “Even though it’s not the same Walmart where it happened.” She doesn’t buy it. “We can’t let fear determine how we live our lives.”

She rolls her eyes.

We are greeted at the entrance by armed security guards, and two police officers. The tension is palpable. The place is quiet, almost completely empty, shoppers are scarce. The few who are there keep to themselves. The emptiness only makes it that much harder to distract oneself. In the silence, my mind invents a story. I am re-imagining the incident as I walk the aisles. People scrambling for their lives. Gunshots. Blood. Screams. How would I have reacted? What would I have done? I like to think I would’ve done anything to protect my children. I like to think others would’ve done anything to protect us. And I believe they would have. I believe in the basic goodness of people. I need to believe in this, otherwise I’ll go around the world paranoid. And I refuse to be a prisoner of my own time. I have to get out of my head. We push our cart around a corner and find ourselves in front of a white couple wearing shirts that read: El Paso Strong, and Amor Para El Paso. And it brings me some sense of relief. The word Amor. The sign I didn’t know I needed. What the presence of that word alone can do for you in just the right moment, under the right circumstances.

“Where’d you get your shirts?” I ask them.

They’re surprised by my question. We talk for several minutes. Later, I will not recall what about. But I know it wasn’t about the shooting. Maybe it was about the weather. The heat is unbearable these days. The monsoons offer no solace. In this moment, everything we say sounds like a metaphor. What I pay attention to most is the essence of our exchange. A kind of closeness. As if we are mutually looking for reasons to communicate with one another. Strangers in our city. If for no other purpose than to remind ourselves that we are connected. It’s a brief but necessary exchange. And I can see that it lifts Rumi’s spirits. They even shake our hands as we leave. Any excuse to touch.

May 9, 2019

It is three months before the Walmart shooting. President Trump speaks at a rally in Panama City Beach, Florida. In response to thousands of Central American families who are trekking to U.S. borders to seek safety and asylum, he says: I mean when you have 15,000 people marching up, and you have hundreds and hundreds of people, and you have two or three border security people that are brave and great…and don’t forget, we don’t let them…we can’t let them use weapons, we can’t. Other countries do. We can’t. I would never do that. But how do you stop these people?

Woman from the crowd: Shoot em!

The crowd laughs.

President Trump: (Laughing) That’s only in the panhandle you can get away with that…

The crowd erupts in applause.

Trump pauses for comedic effect, tugs his lapel, smirks, repeats: Only in the pandhandle!

The crowd roars. They’re eating it up.

Florida is a panhandle state.

So is Texas.

In Texas, the years between 1910 and 1920 were known as “La Matanza,” or sometimes, the “Hour of Blood.” It was a decade long, state sanctioned, era of ethnic cleansing, in which the Texas Rangers lynched, dragged, shot, and killed over 5,000 brown skinned people and buried them in mass, unmarked graves. It was open season. Brown families lived in constant fear of white men mounted on horses wielding rifles with the authority of a badge. Some historians may take issue that I am not specifying “Mexicans” here. But let’s get this straight, a brown body was a brown body, nationality be damned. Still, other historians will argue the numbers and the years, but that’s only because the records have been mostly redacted on this dark chapter, blacked out, burned, or disappeared. Besides, the exact number isn’t the issue. One is too many.

A panhandle is not the hottest part of the pan. The hottest part is where the pan kisses the flame. This is where my children and I live.

Although his Manifesto says “Hispanics,” the Walmart terrorist does not actually mean “Hispanics.” Let me clarify. His mission is specifically to shoot a group of people whose skin pigmentation is darker than white. How much darker? He will decide. When he enters the store he will not be requiring documents for proof of race, citizenship, or nationality. He will walk in with one goal and one goal only—to seek out brown bodies and “shoot ’em” indiscriminately. This is what hate does. It has no order. Hate claims to have a target, but it makes no promises. If amidst the terror, one person should step forward and declare, “I’m not Hispanic, I’m white!” I assure you this will not be enough. Your ethnicity will not spare you from hate. In fact, it was not enough. Not that day in that Walmart. Because it did not spare a grandmother named Margie Reckard, or a beloved uncle named David Johnson. Nor did it spare a victim named Alexander Gerhard Hoffman Roth, who was born in Germany. And what is racism if not hate justified by an idea. Racism spares no one. Don’t be fooled, racism has no loyalties, except to the idea. Not even the racist himself is exempt. Especially the racist. This is why he or she will ultimately die for the idea.

In the months following, the Cielo Vista Walmart was shut down and a chain link fence was lassoed around the perimeter. Large green tarps were draped over it, blocking view of the scene. A redaction on a grand scale. But this city is no stranger to walls. We know what’s on the other side. Spontaneously, people turned the fence into a memorial site. Not unlike others we’ve seen in cities across the country: Dayton, Gilroy, Boulder, Buffalo. The list grows.

The store itself was renovated. The interior gutted, reshaped. If it looks like a different store, customers will return. Sales will continue. As a show of solidarity, the corporate giant would hire an architect firm from Arkansas to design a more permanent memorial. A bronze-colored cylinder made of aluminum, which stands 30 feet tall and illuminates at night, is what they came up with. They call it the “Grand Candela.” Big Candle. The names of the victims do not appear anywhere on or around it. Nor the names of the other two dozen wounded survivors. It stands, out of the way, in a parking lot that overlooks Interstate 10. Unless you know exactly where to look, it’s an unnoticeable structure, with no gravity. It was designed with this in mind. A memorial that does not draw attention to itself. They should have named it the “Grand Pacifier.” As far as memorials go, it’s a lackluster gesture for what has come to be known as “the deadliest attack on Latinos in modern U.S. history.”

November 4, 2019

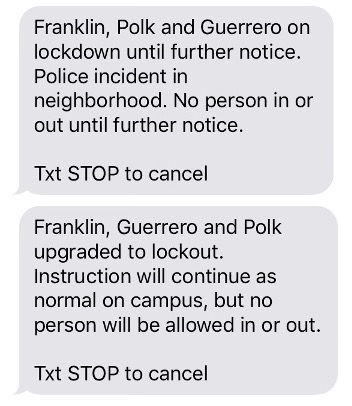

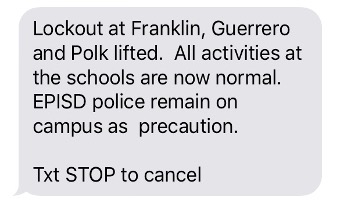

Three months after the Walmart massacre, El Paso is still tender. The wound slow to heal. But at least we’ve managed to stop holding our breath. Our children have finally begun settling back into school. The El Paso Independent School District assures us it has implemented further safety measures. Police officers guard the schools, as well as the entrances of all Walmarts. Rumi is once again thriving at Franklin High. The days are calm. We don’t forget. But we do go about our lives. It’s always there. Some days less so. Some days we feel normal again. Like today. Today is just another regular Monday. But then, two texts appear, just minutes apart:

. We are scared. I am scared.

We live in constant fear. I live in constant fear.

We don’t know what’ll come next, or from where.

We I only know that it will come.

I’m aware that I’m a brown man in America. I’m aware. We are aware.

And I’m aware that I’ve historically been erased at any given moment. We have

This is what I’ve learned to live with, what we’ve learned to live with.

I am aware that my children are now aware of this too. We are They’re aware.

I am aware of how much awareness I we must have in order to simply exist

in this country.

And then—

Breathe.

This is where the chapter was supposed to end. On a single ‘breath’ left alone on white space. But the day that I wrote the word “Breathe” was May 26, 2022. And on this day, perhaps at the exact moment I was writing that word, nineteen brown school children and two brown teachers were being slaughtered by a brown man in the small town of Uvalde, Texas, just south of here. Meanwhile, nineteen mostly brown cops stood outside the brown door and did nothing for more than a brown hour, except listen to the screams of the brown children and the gunfire. Strike that, they did act. But only upon the brown parents of the brown children who were desperately pleading for them to, Do something! Tasing them. Cuffing them. Holding them at gunpoint. This is true. The brown cops. The brown parents. The brown children. The brown shooter. Have we bought into our own dehumanization? Have we become invisible to ourselves? La Matanza is alive and well in Texas. We are living in the New Hour of Blood.

Tim Z. Hernandez is an award-winning author, research scholar, performer, and professor. His debut collection of poetry, Skin Tax received the 2006 American Book Award, and the James Duval Phelan Award from the San Francisco Foundation. His debut novel, Breathing, In Dust was featured on NPR’s All Things Considered, and went on to receive the 2010 Premio Aztlan Prize. His second collection of poetry, Natural Takeover of Small Things received the 2014 Colorado Book Award, and his novel, Mañana Means Heaven, went on the receive the 2014 International Latino Book Award in historical fiction. His latest book, All They Will Call You, is a genre bending work of non-fiction based on the song by Woody Guthrie, “Plane Wreck at Los Gatos (Deportee).” This book is the first installment of The Plane Crash Series, a project that he considers his life’s work. For this work he was awarded the coveted Luis Leal Award for Distinction in Chicano Letters by the University of Santa Barbara in 2018.